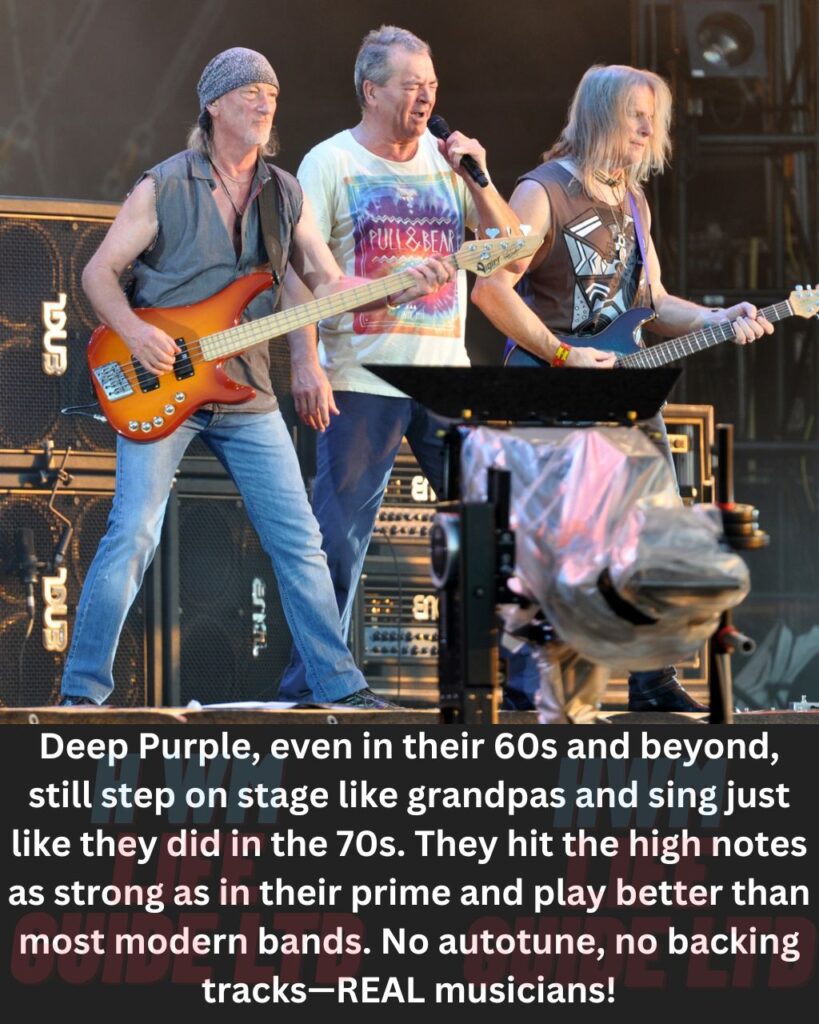

No autotune, no backing tracks—just five musicians walking on and detonating a classic. “Highway Star” at Wacken captures Deep Purple raw, loud, and impossibly alive, the kind of performance where you hear amps breathing and cymbals spilling into vocal mics. It isn’t a stitched studio artifact; it’s the real thing, recorded in front of an ocean of fans who came for guitar, Hammond, and a singer daring the high notes. Dang, they sound GREAT!!

The setting matters. Wacken Open Air is a small city of black shirts and raised hands, a festival so large the air itself seems to vibrate. On that stage, “Highway Star” feels like architecture—riffs as scaffolding, choruses as weather fronts moving through a valley of people. You don’t watch it so much as step inside it, where crowd roar becomes part of the arrangement and risk reads like voltage.

The lineup is late-era Purple at full command: Ian Gillan on vocals, Steve Morse on guitar, Don Airey on Hammond and keys, Roger Glover on bass, and Ian Paice on drums. What they do best is conversation. The songs become five-way arguments full of laughter and side-glances, built on decades of shared reflexes. They trust muscle memory more than click tracks, and it shows in the way every section breathes.

“Highway Star” is a perfect vehicle for that approach. Born on the 1972 album Machine Head, it’s a speed-leaning hard-rock sprint with classical DNA—long, worked-out organ and guitar solos, rapid arpeggios, and a structure that invites virtuosity without losing the engine-room pulse. On a huge stage, those ingredients expand without thinning; the classical curves turn aerodynamic, and the rock rhythm grows taller instead of merely faster.

From the first bars, Paice and Glover lay steel rails. The tempo is urgent but unhurried, that rare pocket where speed feels roomy. Paice’s right hand flickers like a sewing machine while his kick writes sentences; Glover locks to the drum phrasing with a tone that says locomotive, not lawnmower. That foundation lets the soloists fly without fear of the ground falling away.

Then comes Gillan, headline drama and defiant stamina. He doesn’t hedge or rewrite melodies to hide the high parts. He goes at the song in the fierce, original register, pacing his breaths so the big vowels land like fireworks. He’ll let a note fray at the edge and then snap it clean again, a living masterclass in control. Long live Mr. Gillan—still selling danger and joy in the same phrase.

Steve Morse refuses to impersonate Ritchie Blackmore, and that’s the point. He honors the blueprint—the Bach-like articulation, the racing sequences—but bends it with fluid legato and modern precision. His tone cuts without shrieking, and his lines arc like a pilot tracing loops over the field. It’s respectful, not reverent; forward-leaning without erasing the fingerprints that made the solo a rite of passage.

On Hammond, Don Airey channels Jon Lord’s baroque ferocity while stamping every phrase with his own signature. The organ doesn’t sit behind the guitars; it wrestles them, grinning. Drawbars growl, Leslie speakers spin, and those stacked chords crash like church bells in a thunderstorm. When organ and guitar trade lines, it’s two languages describing the same storm from different hills.

Because the rhythm section never lets the floor sag, the song’s hardest trick—feeling fast and heavy at once—lands. Many bands chase speed and lose mass; Purple makes velocity feel thick-walled. Paice drags the snare by half a molecule to make the groove swagger; Glover lengthens notes just enough to glue the kicks. The result is a sprint that still hits like a hammer.

Production choices keep it honest. You can hear the stage: mic pops, monitor squeals, cymbal wash hugging vocal mics. The mix leaves headroom so the crowd remains part of the music rather than wallpaper. It’s not a “fix it in post” polish job; it’s a preservation of risk—of humans aiming high in real time, winning more often than not because they’re not afraid to leave fingerprints.

Set context sharpens the impact. “Highway Star” arrives near the top, a dare and a handshake all at once. Around it, the band tours eras—“Into the Fire,” “Perfect Strangers,” “Lazy,” the big anthems—so you feel the through-line from early-’70s steel to modern muscularity. Later, a guest steps in for “Smoke on the Water,” a nod to shared lineage that sparks its own ovation.

The crowd becomes an instrument. Wacken’s call-and-response turns choruses into civic events, voices stacking until they feel like scaffolding around the band. You hear strangers become a choir on the spot, vowels blooming over open air. That communion is what the “no backing tracks” promise buys: the thrill of not knowing exactly how big the final note will be until everyone jumps.

Context matters beyond the night, too. The band was deep into a global run, road-hardened from months of stages and carrying fresh studio momentum. New songs sharpen old instincts. You can sense it in transitions that click like seatbelts and in the way solos stretch a breath longer than the record but snap back to the chorus like a rubber band finding home.

For anyone who loves real singing, the lesson is obvious. THAT IS GREAT VOICES AT WORK RIGHT THERE. Gillan picks his battles and still chases the skyline, which is why the big notes feel like victories and not obligations. The organ and guitar answer like teammates shouting across a finish line. You can almost hear the smiles through the microphones.

Fans who crave authenticity will find their manifesto here. No autotune, no backing tracks, no ghost players hiding behind the curtain—just five names printed on the ticket and five shapes on the stage. When a note wobbles and then straightens, that’s humanity, not a bug. When a risk pays off, the payoff is yours, too, because you felt the wire underfoot.